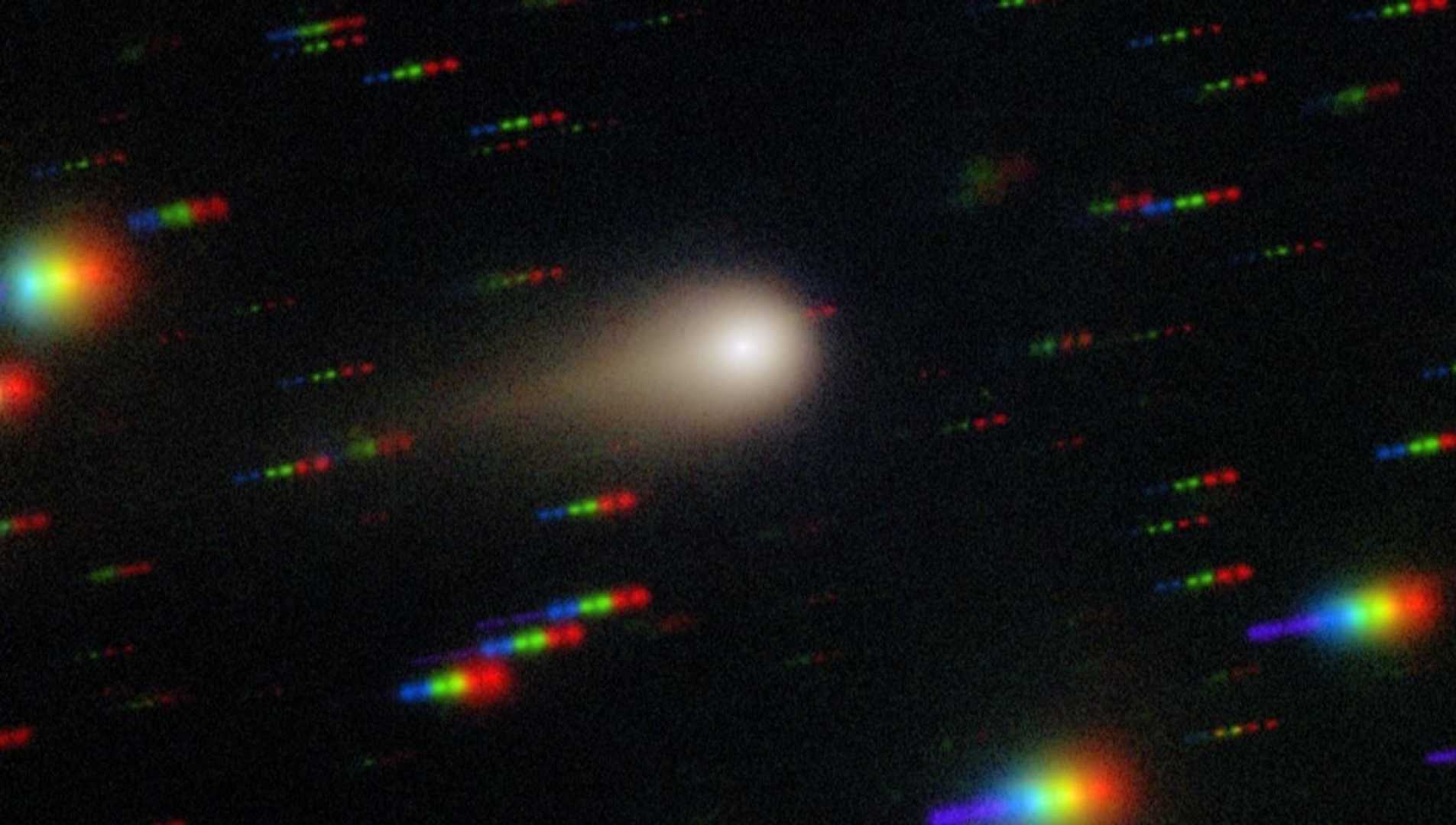

Comet 3I/Atlas Reveals Surprising Water Emissions in Space

AUBURN, Alabama — Comet 3I/Atlas continues to surprise scientists with new findings. Researchers at Auburn University analyzed data from the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory and discovered that the comet is producing hydroxyl (OH) emissions, indicating the presence of water on its surface.

This groundbreaking analysis was detailed in a recent study. Hydroxyl compounds emit a unique ultraviolet signature which is difficult to detect from Earth due to atmospheric interference. Thus, the researchers utilized the Swift Observatory, a space telescope that circumvents these limitations.

Water is a common component throughout the solar system, and its chemical reactions are key to understanding celestial bodies and their interactions with solar heat. The detection of water on 3I/Atlas allows researchers to study it alongside traditional comets, potentially offering insights into comets from other solar systems.

“When we detect water—or even its faint ultraviolet echo, OH—from an interstellar comet, we’re reading a note from another planetary system,” said Dennis Bodewits, a physicist at Auburn University involved in the study. “It tells us that the ingredients for life’s chemistry are not unique to our own.”

Comets typically orbit stars, but 3I/Atlas is an interstellar object. While near a star, comets become active as their frozen components warm up and sublimate into gas. However, data indicates that 3I/Atlas was producing hydroxyl emissions even at a distance over three times farther from the sun than Earth, where temperatures are usually not warm enough for such sublimation.

This unusual activity showed that the comet was leaking water at an estimated rate of 40 kilograms per second, comparable to a hydrant at full flow. This suggests that 3I/Atlas may have a more complex structure than typical comets, possibly due to small ice fragments detaching from its nucleus and vaporizing upon exposure to sunlight.

“Every interstellar comet so far has been a surprise,” said Zexi Xing, an Auburn University researcher and co-author of the study. “‘Oumuamua was dry, Borisov was rich in carbon monoxide, and now ATLAS is giving up water at a distance where we didn’t expect it. Each one is rewriting what we thought we knew about how planets and comets form around stars.”

Researchers say that these findings could significantly reshape our understanding of cometary processes and their origins.