News

Cities Accused of Miscalculating Property Transfer Taxes in Quebec

(Montréal, Canada) A request for a class action, filed on October 31, claims several cities in Quebec, including Montréal, Laval, Longueuil, and Brossard, improperly calculate property transfer taxes. The allegation suggests that thousands of real estate transactions in these cities have been affected by inaccurate calculations.

The dispute centers on the assessment basis chosen by the cities for calculating the transfer taxes, commonly known as the “welcome tax.” When a property transaction occurs, new buyers are charged these taxes. Across Quebec, the basis for these taxes is the highest of the following values: the sale price or the property’s assessed value.

The highest value is then multiplied by a “comparative factor”—currently set at 1.08 in Montreal and 1 in the other cities involved. The transfer taxes are applied to this final amount. However, issues arise when the calculation is based on the value from the municipal assessment rolls, which are established every three years. Many cities choose to spread increases over time rather than applying them as a lump sum.

David Bourgoin, the attorney for the plaintiffs, explained, “Instead of saying that the property increased by $150,000 in the first year of the next role, they can spread the increase over the three years, which is permitted under municipal taxation law.” For example, if a property’s value increases by $150,000 from 2026 to 2028, the increase would be phased in by $50,000 each year until 2028.

Currently, cities using this phased-in approach are applying it to calculate property tax bases, but they do not use it for calculating transfer taxes. The class action argues that buyers end up paying transfer taxes based on future property values.

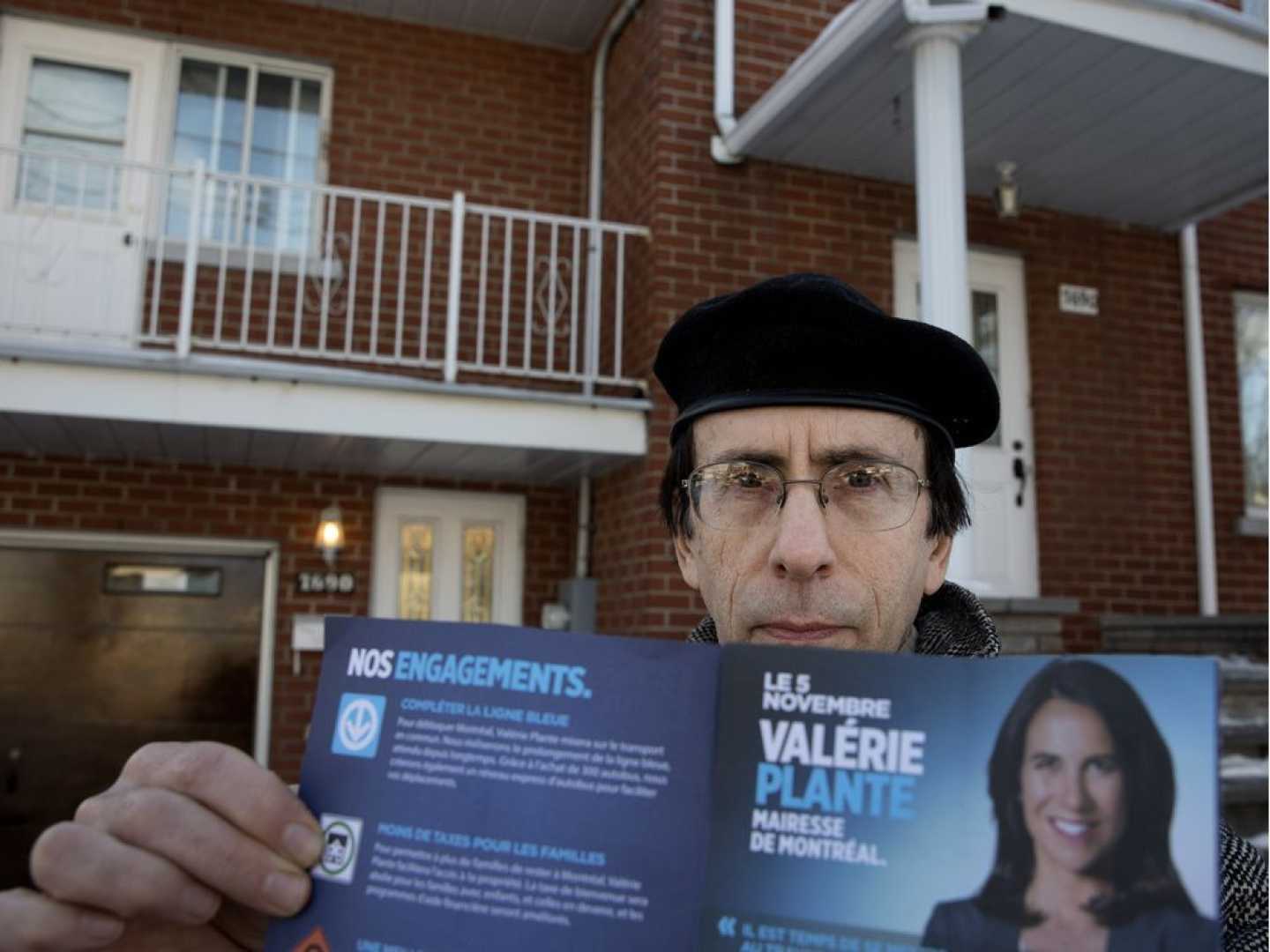

In the class action, Pierre-Luc Pelletier, one of the plaintiffs, purchased a property in Rosemont in 2024 for $600,000. The City of Montreal assessed his property at approximately $755,000 for the 2023-2025 period. Under the city’s resolution allowing for phasing, Pelletier’s adjusted taxable value in 2024 is $698,000. His transfer tax, based on the assessment roll value, amounted to $12,074. If considered using the phased value, he would have paid $10,829, a difference of $1,245.

The class action must first be deemed admissible by a Quebec Superior Court judge before any further proceedings occur. Bourgoin stated, “The judge has to decide if it’s serious enough for the second stage.” If approved, evidence will be presented in court, and settlement between parties remains an option at this stage.

It is important to note that all affected buyers are automatically included in the class action without needing to register. While the action only targets transactions in these four cities, any municipality can choose to adopt a phased approach before approving its budget. Bourgoin acknowledged that similar issues could arise outside the metropolitan area, noting that major cities like Quebec and Lévis did not have this phasing in place.

In April 2025, Quebec court ruled in favor of buyers who argued transfer taxes should be calculated based on adjusted taxable values rather than the assessment rolls, resulting in a $5,600 payment by the City of Montreal to the plaintiffs.