News

Canada’s Budget Watchdog Releases Updated Carbon Tax Analysis

Canada‘s independent budget watchdog has revisited its analysis of the federal carbon tax and rebate system, correcting a previous oversight and reaffirming some earlier results. According to the revised study by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), a significant number of Canadians will continue to receive more in carbon tax rebates than they pay under the tax itself.

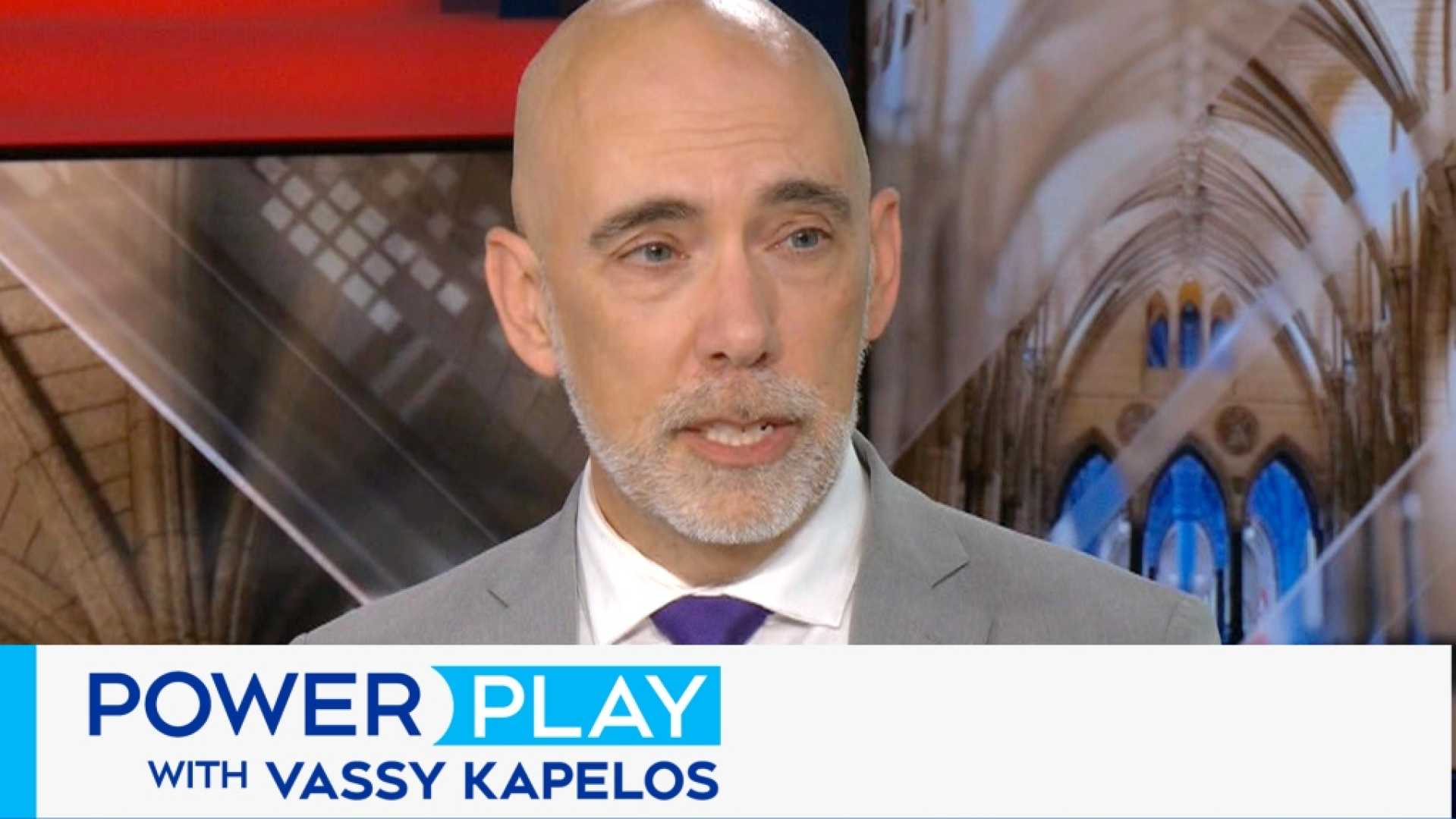

The reassessment, released Thursday by Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux, was necessitated by what the office termed an “inadvertent error” in previous analyses. This error involved mistakenly incorporating the industrial carbon pricing system applicable to large emitters such as those in the oil, gas, and steel sectors, thus skewing prior conclusions.

The updated report finds that, when considering average household expenses—including the consumer fuel levy, the goods and services tax (GST) charged, and indirect costs attributable to the carbon tax—households will, on average, experience a net financial gain by the fiscal year 2030-31.

However, despite these net gains in rebate receipts, the PBO underscores that when broader economic impacts like effects on employment and investment income are included, households might face net costs. Giroux noted that “given that the fuel charge lowers employment and investment income, which makes up a larger share of total income for higher-income households, their net cost is higher.”

The resurgence of this complex fiscal scrutiny has reignited political debate. Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre has been vocally critical, reiterating his pledge to “axe the tax” if he gains office, arguing that the carbon tax will only impoverish Canadians. He has called for what he terms a “carbon tax election,” highlighting that this report “confirmed” his position on the economic impact of the tax.

In response, Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault defended the system, stating, “The system gives more money back to Canadians through rebates than they lose to the carbon tax.” Guilbeault emphasized the report’s role in clarifying misconceptions, asserting that “carbon pricing is the most cost-effective way to fight climate change.”

The corrected analysis estimated reduced net cost projections in regions like Alberta, where previous forecasts indicated much higher burdens. The new report now estimates the average household net cost at $697 by 2030-31, down from $2,773 projected earlier.

The PBO clarified that its analysis does not factor in the long-term environmental benefits of reduced emissions or the broader economic impacts from climate change. It also does not evaluate alternative policy approaches.

This ongoing political contention reflects broader issues, as noted by Alex Cool-Fergus, national policy manager for Climate Action Network Canada, who stated, “By continuing to focus on carbon pricing, we are collectively ignoring the elephant in the room: the costs of runaway climate change.” Cool-Fergus pointed to the increasing severity of climate-related disasters as a reminder of the stakes involved.

As the carbon tax looks set to rise further annually until reaching its target of $170 per tonne by 2030, the debate is likely to persist, with both political proponents and critics continuing to use these economic analyses to bolster their arguments.