News

Weak La Niña Emerges Late, Impacting US Winter Weather

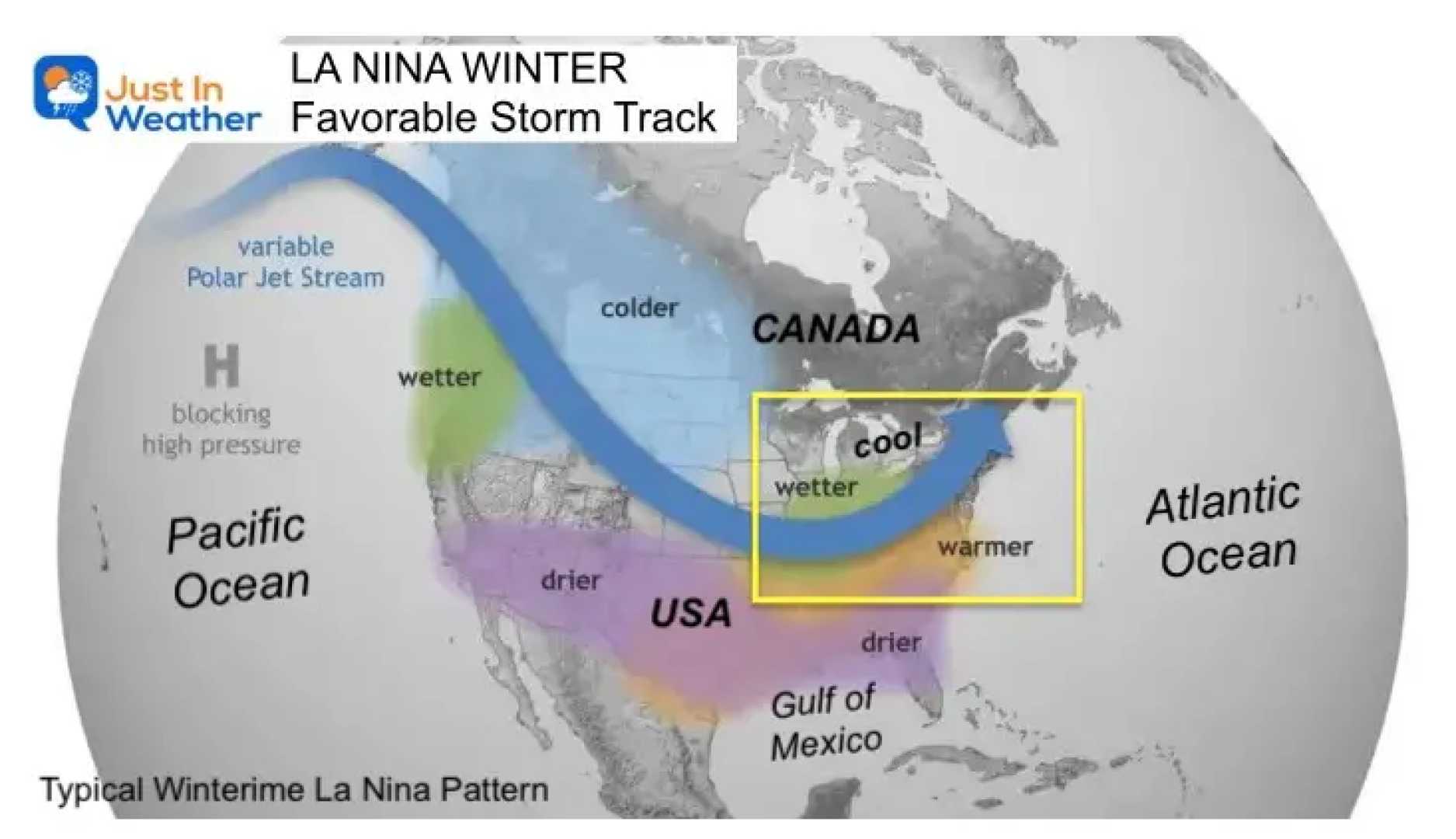

La Niña, the climate pattern known for influencing winter weather across the United States, has finally emerged but with a significant caveat: it is weaker than usual and arrived late in the season. Despite its diminished strength, the phenomenon has already begun shaping weather patterns, particularly in California and the Midwest.

La Niña is characterized by cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, which alter atmospheric circulation and impact global weather. This winter, the pattern’s late arrival and weakened state have limited its typical influence, according to Emily Becker, a research professor at the University of Miami and a lead author of NOAA‘s ENSO blog. “It is really getting started right at the time when it would normally be peaking and beginning to dwindle,” Becker explained.

In California, La Niña’s effects are starkly visible. Northern California has experienced unusually wet conditions, while Southern California remains dry, contributing to heightened wildfire risks. Meanwhile, the Midwest has seen above-average precipitation, with cities like St. Louis, Indianapolis, and Cincinnati recording some of their wettest winter starts in recent history.

However, La Niña’s influence is not uniform across the country. The South and central U.S., typically drier and warmer during La Niña winters, have instead faced periods of heavy rain and snowstorms. This variability underscores the complexity of weather systems and the role of other atmospheric factors.

The Climate Prediction Center forecasts that this weak La Niña will persist through April before transitioning to neutral conditions. While warmer-than-normal temperatures are expected across much of the southern and eastern U.S., cooler conditions are likely in the Northwest. Wetter weather is anticipated in the Midwest and Northeast, potentially leading to snowstorms in early spring.

La Niña’s delayed emergence is partly attributed to record-high global ocean and air temperatures in 2024, which made it difficult for the equatorial Pacific to cool sufficiently. This year is on track to be the hottest on record, further complicating traditional climate patterns.

Despite its weakened state, La Niña’s impact on winter weather remains significant, though less predictable. As Becker noted, “If La Niña were stronger, I would have more confidence that the rest of the winter would closely resemble La Niña’s expected impact.”