News

Tensions Rise Over Elver Fishing Rights in Nova Scotia

HALIFAX, Nova Scotia — Tensions escalated on Sunday night as two commercial fishers harvesting baby eels found themselves halting operations when a large group of Indigenous harvesters arrived at their fishing site. The incident highlights ongoing disputes surrounding new federal regulations on elver fishing.

Suzy Edwards, an employee of Atlantic Elver Fishery, recounted that a fisher from Sipekne’katik First Nation indicated they were making a statement against Ottawa’s recently imposed quota distribution system. “We can’t fish basically is what we’re saying,” Edwards stated after the encounter. “There are too many people there, and we can’t go there and dip [our nets].”

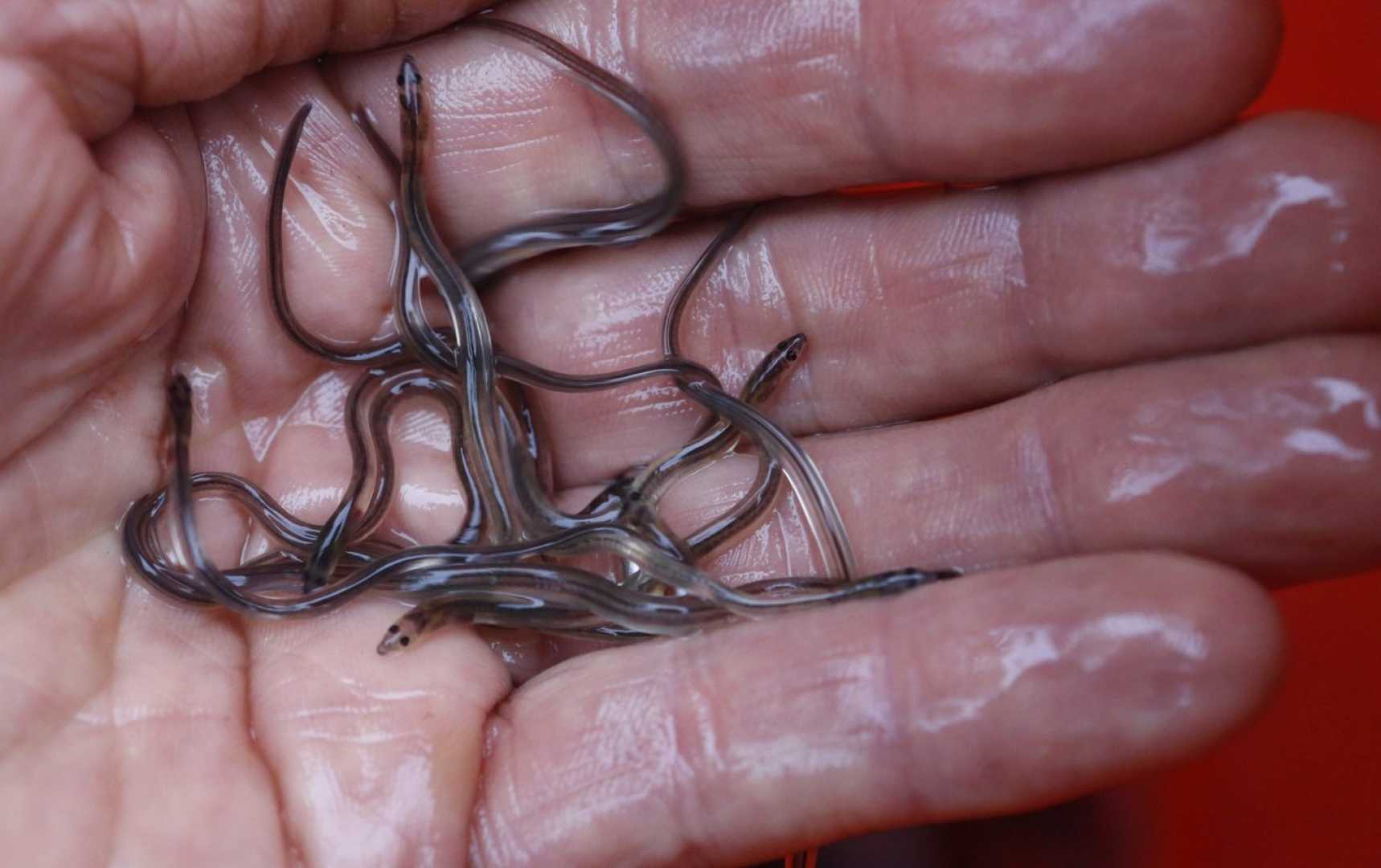

The federal system allocates fishing quotas to licence holders, including 20 First Nations recognized as new entrants. These quotas are based on community population, and specific rivers are designated for harvesting the tiny eels known as elvers. Last year, Ottawa announced that 50% of the allowed catch of 9,950 kilograms would be transferred, without compensation, from long-standing commercial licence holders to these First Nations.

The market for elvers is lucrative, with prices ranging from $1,700 to $5,000 per kilogram as they are primarily exported to China for aquaculture.

Edwards and her fishing partner, Alan MacHardy, stated that under the new regulations, their company has retained federal licensing to operate on the Hubbards River. They had fished quietly at the site for over a week without incident, but were surprised to see the parking area filled with trucks as approximately 50 Indigenous fishers set up their nets on Sunday evening.

<p“Even if we were to go down and dip, there’s no place to do so as there’s too many people… We lost the night of fishing,” MacHardy expressed.

Chief Michelle Glasgow of Sipekne’katik did not respond to a request for comment on the matter. In a recent correspondence to the federal Fisheries Department, Chief Bob Gloade of Millbrook First Nation emphasized that his community, along with Sipekne’katik and two others, is asserting its jurisdiction to establish independent elver fishing plans.

According to Gloade, this claim is supported by a 1999 Supreme Court of Canada decision, which established that First Nations fishers have the right to develop their own regulatory systems to sustain a moderate livelihood. “We are not regulated by your colonial commercial licensing schemes, nor do we accept your proposed management plan,” Gloade wrote.

However, Doug Wentzell, regional director general for the Fisheries Department, informed several First Nations through a March 18 letter that legal precedents support Ottawa’s authority to define fishing quotas and areas. He referenced the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Marshall case, which affirmed Ottawa’s role in fishery regulation and made it clear that sustainable fishery practices depend on a centralized controls system.

Wentzell noted that while the federal regulations aim to balance Indigenous fishing rights and conservation needs, he acknowledged limited success in consulting with Chief Glasgow’s community regarding the new framework. He mentioned that five rivers have been designated for harvesters from Sipekne’katik, and expressed a willingness to consider additional rivers of interest for the 2025 fishing season.

Edwards and MacHardy had initially felt optimistic that the previous year’s chaos surrounding the fishery, which resulted in complete closure, was behind them. “We felt very hopeful up until this point because people were staying away. We said, ‘Maybe this is working. Maybe the plan is working.’ And we drove up today, and what we saw was like a punch in the gut,” Edwards commented.