Health

Childhood Vaccine Response: New Research Uncovers Persistent Variation

A new study published today in Pediatrics sheds light on the long-standing observation that children do not respond equally to vaccines. Researchers from the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute have found that a significant number of children, up to 10% or more, exhibit consistently low antibody responses to multiple vaccines, a phenomenon termed ‘very low vaccine responder’ (vLVR) status.

“Eight years ago, our group described this finding of low responders, children who don’t produce enough antibody after vaccination, which suggests a problem with their immune system,” says Dr. Michael Pichichero, lead author of the study. “Our latest research, which followed these children over time, confirms that this vLVR status is persistent and the children remain low responders, even after booster doses.”

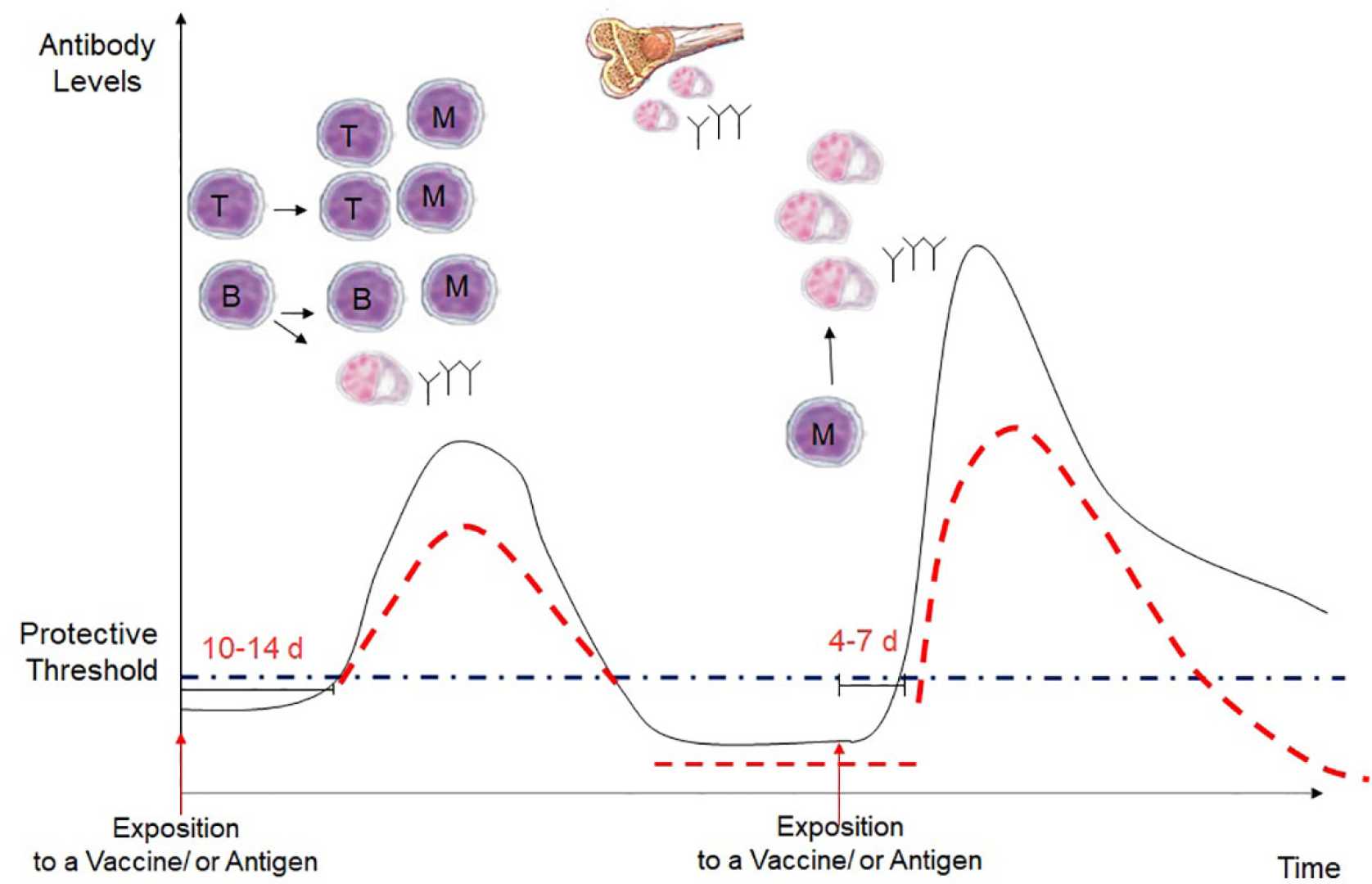

This study focused on 357 children who had received a primary series of routine childhood vaccines and were tracked for antibody levels at various time points from age 6 months up to age 36 months. Detailed immune profiling was conducted to assess the performance of different immune cell types, including B cells that produce antibodies, T cells that help fight infections, and antigen-presenting cells that trigger an immune response.

Based on these findings, the researchers classified children into four vaccine response groups: vLVR, low vaccine responder (LVR), normal vaccine responder (NVR), and high vaccine responder (HVR). The goal of the study was to understand how these groups changed over time as children received booster doses.

“Surprisingly, we found that the vaccine response group a child belongs to remains relatively stable over time,” explains Dr. Pichichero. “This means that a child who starts out as a vLVR is likely to remain a vLVR, even after booster vaccinations. This highlights the need for personalized vaccination strategies for children who have consistently low responses to vaccines.”

The implications of this study are significant for public health. Understanding why some children have weaker immune responses to vaccines can lead to more effective interventions, such as tailored vaccination schedules, dosage adjustments, or alternative vaccine formulations. This research continues to provide valuable insights into the complex interplay between genetics, immunity, and vaccine effectiveness.