News

Severe Winter Weather Linked to Climate Change, Study Finds

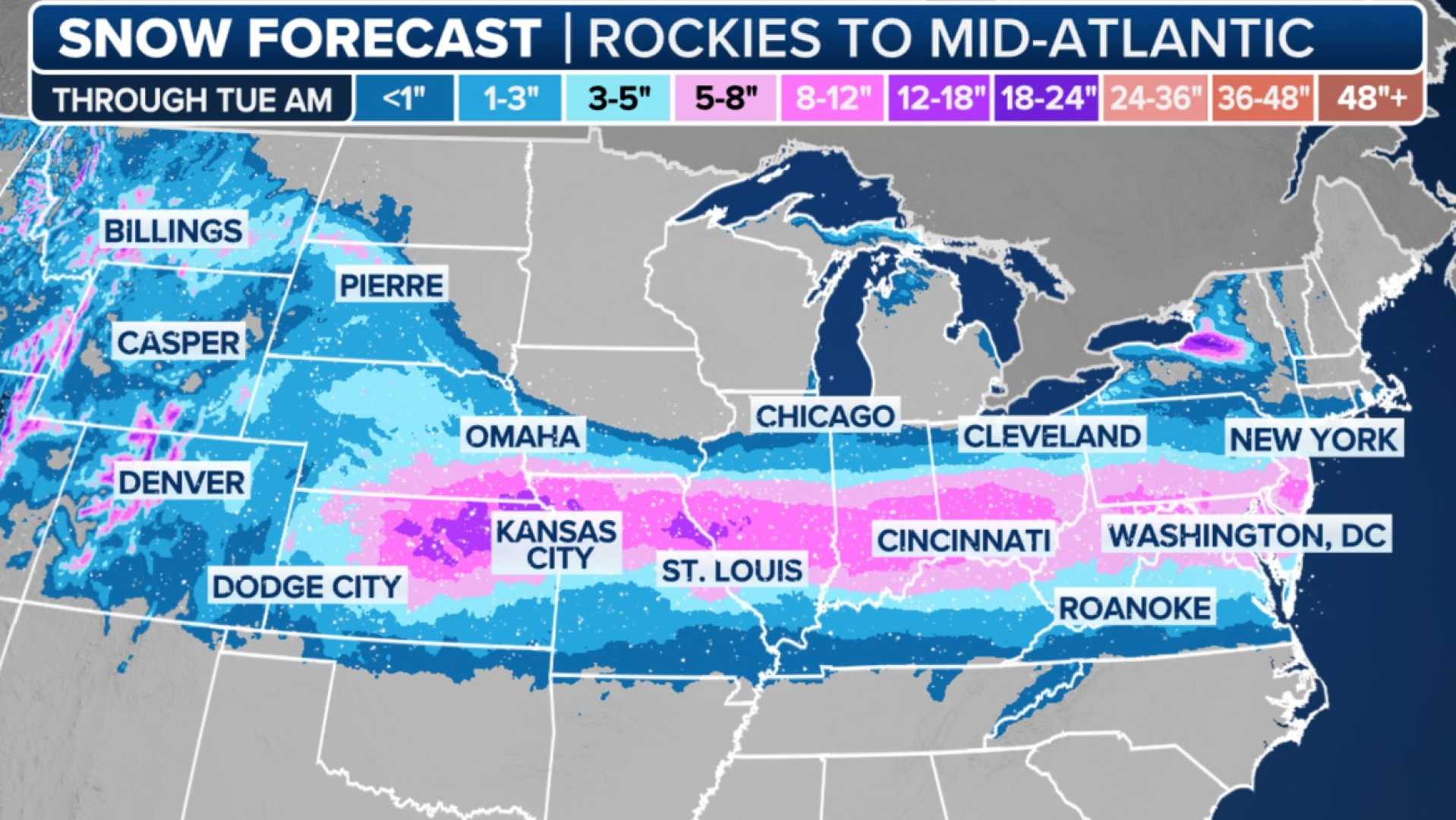

A second bout of severe winter weather is set to pummel the central United States with freezing temperatures and icy conditions, forecasters warned this week. This comes just days after a massive winter storm, traveling from Kansas to New Jersey, dumped upwards of a foot of snow on some cities, disrupting traffic and knocking out power for hundreds of thousands of households.

A growing body of research suggests climate change is partially to blame. A study published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature last fall found a strong correlation between the warming Arctic and an increase in severe winter weather—including heavy snowfall and subfreezing temperatures. Specifically, the study found that a warmer Arctic results in more frequent severe winter weather in places like the central U.S., Canada, and parts of Asia and Europe.

“We’re seeing that this week,” said Judah Cohen, the study’s lead author and a climatologist at the research firm Atmospheric and Environmental Research. “We had this snowstorm from Kansas City all the way to Washington, D.C. And now it could snow in Texas.”

Cohen’s study expands on his earlier research, which used meteorological data from U.S. weather stations. By comparing that dataset to European “gridded data” collected from around the world, Cohen said, he and his colleagues were able to find “a robust and nearly linear relationship” between the temperature of the Arctic region and the frequency of harsh winter weather at a global scale.

The connection, Cohen said, lies in the polar vortex, a swirling body of frigid air that circles the Arctic. A second polar vortex swirls over Antarctica. Typically, that cold air is contained by a fast-moving current of air known as the jet stream. The speed of that current is typically propelled by the steep difference in temperature between the cold Arctic air and the warmer air to its south.

But because the Arctic is warming nearly four times faster than the rest of the world, the difference in those air temperatures is shrinking. That can destabilize the jet stream more frequently and allow the frigid Arctic air to escape south into Canada and the central U.S.

The recent study joins a growing body of research that suggests climate change could be increasing the frequency of jet stream disruptions that allow the polar vortex to break out into lower latitudes. Similar polar vortex events have occurred in recent years, including the deadly 2021 Texas winter storm that knocked out power and resulted in hundreds of deaths.

A polar vortex last January also made national news when subzero temperatures caused major headaches for electric vehicle drivers in Chicago. Significantly cold temperatures can reduce battery range by upwards of 41 percent, some studies have shown, though newer EV models are improving in cold weather performance.

Cohen’s study also found that winter weather is becoming more volatile in certain parts of the northern hemisphere like the central U.S., especially in places where snow and freezing temperatures aren’t always expected. Those findings, he said, help to explain the drastic temperature swings that some areas have experienced in recent winters—what many people are now calling “weather whiplash.”

“In Boston, in February 2023, I think we had record warm temperatures. Then we went to the coldest day in 60 years, and then we’re back to record warm,” Cohen said. “It was terrible—water damage or all the pipes bursting.”

Again, Cohen said, that’s explained by the polar vortex and climate change. As winters get warmer on average, the cold temperatures brought about by the polar vortex events essentially get sandwiched between moments of unseasonably warm temperatures caused by climate change.

Still, not everyone is fully convinced by Cohen’s findings. A 2020 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that there was “only low to medium confidence” in such a linkage after reviewing the studies up to that point. And a 2021 study from the University of Exeter in England found that the loss of sea ice due to climate change was likely to cause little disruption to the jet stream through mid-century—10 percent compared to natural variations at most.

“To say the loss of sea ice has an effect over a particular extreme event, or even over the last 20 years, is a stretch,” James Screen, the study’s co-lead author, said while presenting his findings at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union that year.

But Cohen said those studies rely on climate models, while his studies have analyzed observational data—meaning actual temperature and precipitation readings taken at research stations rather than computer simulations. And he believes it’s likely that those climate models are flawed and not capturing the whole picture.

“A warmer Arctic leading to colder winter weather to the south doesn’t seem to make sense at first glance,” he said, “but I think the physics are sound and I think it fits very nicely into what we’re actually observing in our daily lives.”