Health

Experts Call for Better Insulin Overdose Protocols Following Homicides

Clarksburg, West Virginia — Medical professionals may not be prepared to recognize insulin as a weapon in murders, according to forensic pathologist Dr. Paul Uribe. Recent cases in the U.S. highlight the dangers of this difficult-to-detect medication, which was misused by medical professionals.

Uribe, a former military medical examiner, noted that protocols for identifying insulin-related murders are largely absent. “You’re not going to stumble across an insulin homicide,” he said. “You have to have a suspect and you have to look for it.”

While rare, incidents involving insulin killings are staggering. A nurse in Pennsylvania allegedly caused the deaths of 17 patients from 2020 to 2023, while a nurse at a veterans hospital confessed in 2021 to killing seven elderly patients with the drug.

West Virginia state legislators are advocating for emergency rooms to test for insulin in patients with potential insulin poisoning symptoms. However, Jonathan Jones, former president of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, expressed concerns about legislating medical protocols. “The best medical care is provided by properly educated, trained and board-certified physicians and not by legislators,” he stated.

Additionally, Reade Quinton, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners, emphasized the need for better access to information for medical examiners rather than new protocols. The lead author of the West Virginia bill did not respond to requests for comment, but families affected by the crimes support the legislation.

One family affected is that of Michael Cochran, who was killed by his pharmacist wife. “They won’t have to wait for a result like we had to wait,” Cochran’s mother, Donna Bolt, shared about the proposed bill.

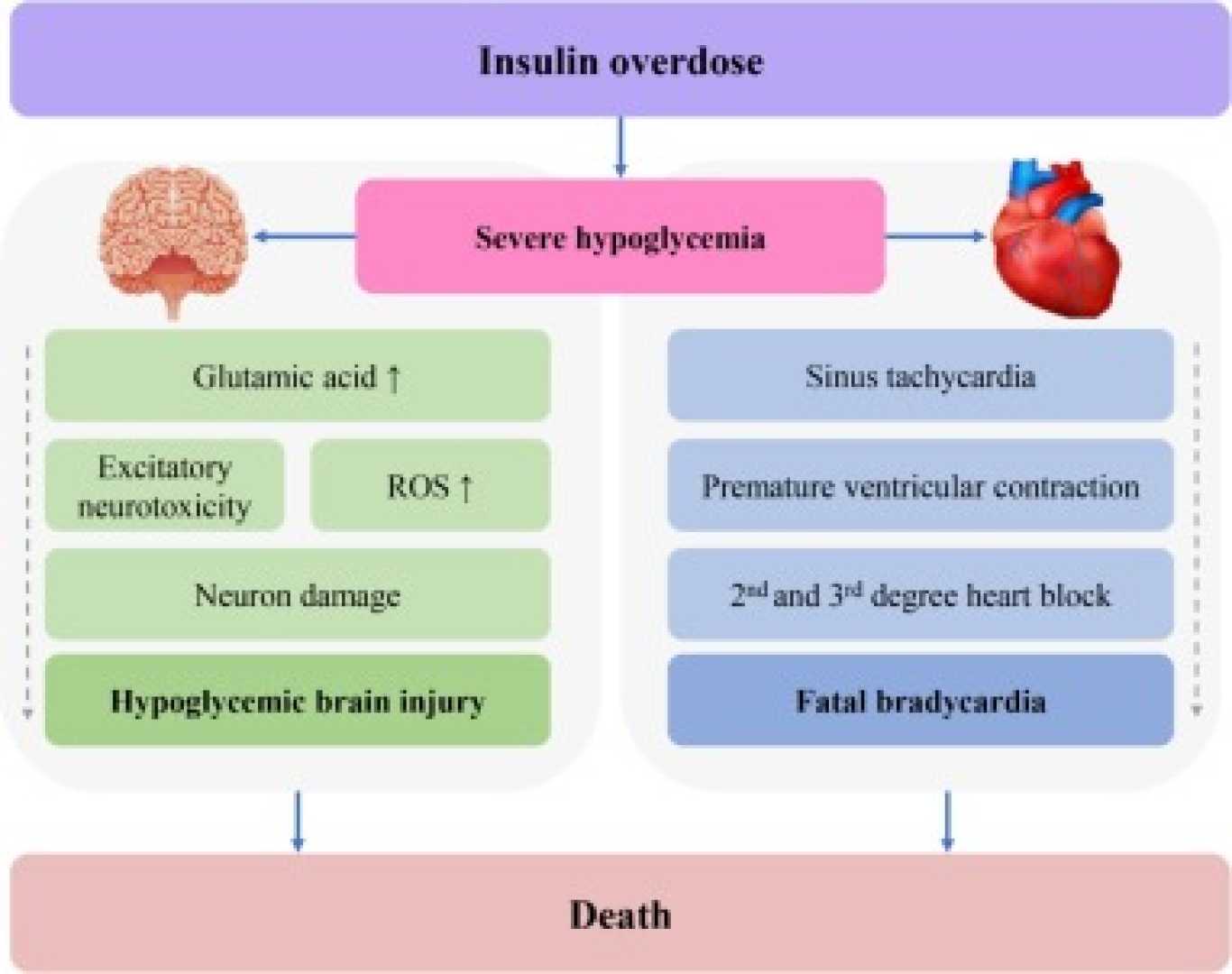

Uribe first encountered an insulin-related homicide in 2018 while investigating mysterious deaths among elderly veterans in Clarksburg. Some victims had severe hypoglycemia due to high insulin levels. “You need to find a smoking gun,” Uribe said.

Pathologists face difficulties as insulin metabolizes quickly in the body. “Once you give glucose, it triggers insulin release, making detection tricky,” he explained. Some tests, like the c-peptide test, require administering quickly before any treatment.

In West Virginia, Uribe investigated the deaths of seven veterans, discovering trace amounts of insulin in victims who had not been prescribed the drug. Reta Mays admitted to injecting lethal doses, leading to her conviction and life sentence.

In another incident, pharmacist Natalie Cochran was convicted of murdering her husband with insulin as part of a scheme to cover financial fraud. Her husband, Michael, had no diabetes history, yet his blood sugar drastically dropped before his death.

Uribe criticized the delayed autopsy and the lack of insulin testing in Michael’s emergency room records, which contributed to the case’s initial dismissal. After two years, the charge was refiled, but most key evidence had decayed.

Ultimately, Uribe ruled Michael’s death as a homicide when no other explanations for his blood sugar drop could be found. At trial, medical experts supported this finding, and Natalie Cochran was convicted of first-degree murder.

These cases highlight the urgent need for improved guidelines on recognizing and addressing insulin overdoses as well as better protocols for medical professionals, according to Uribe. “If you’re able to detect that in the vitreous fluid of someone who’s not a diabetic, that could legitimately tell you something,” he asserted.