News

La Niña Officially Declared, Bringing Wet Winter to Pacific Northwest

SEATTLE — After months of anticipation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has officially declared the arrival of the La Niña climate pattern. This event, characterized by cooler-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, is expected to influence weather patterns across the United States, particularly in the Pacific Northwest.

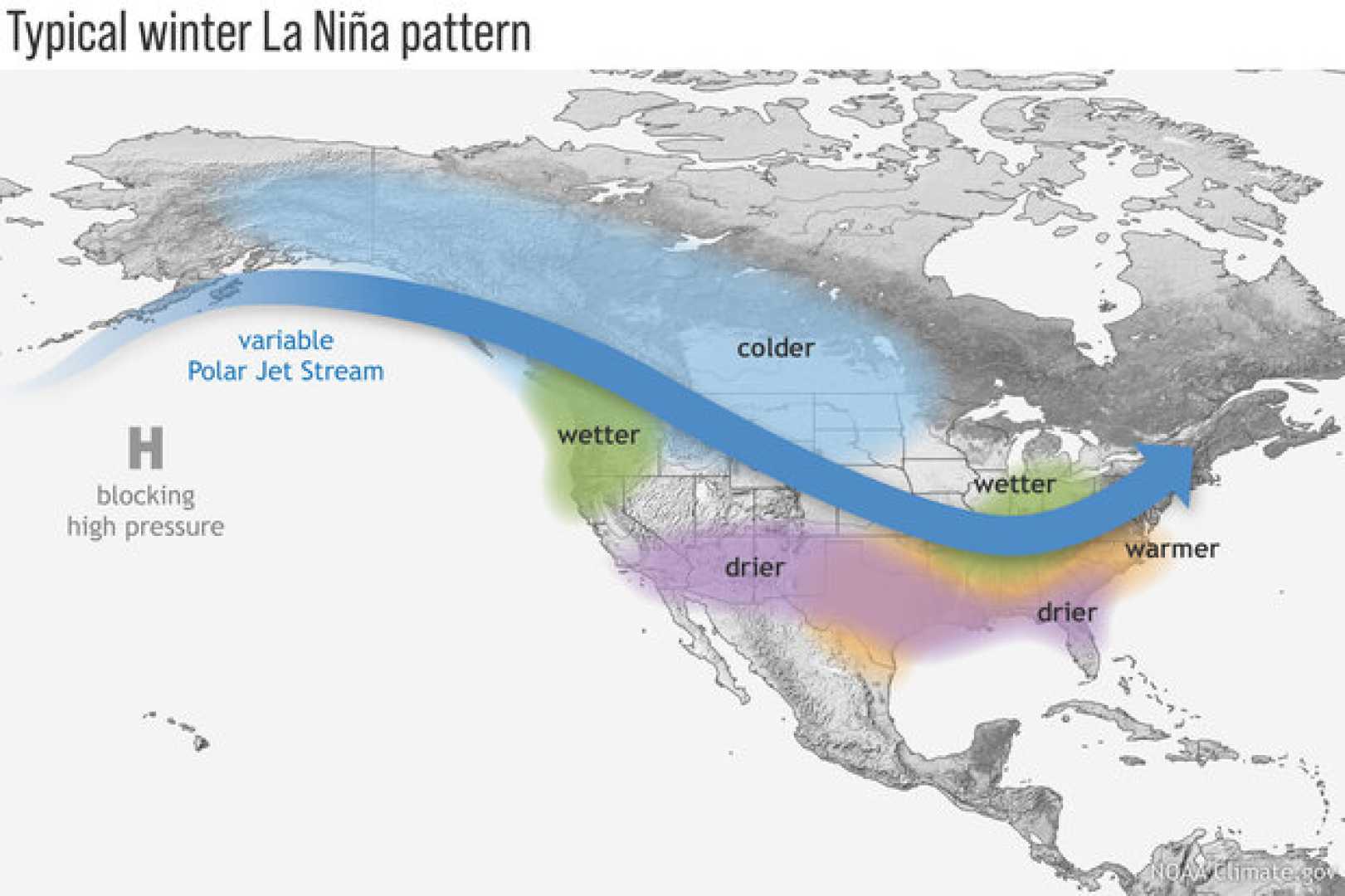

La Niña conditions, which typically alternate with El Niño every two to seven years, were confirmed after Pacific Ocean temperatures cooled to at least 0.5 degrees Celsius below average. This cooling alters the position and intensity of jet streams, which in turn affects storm systems and precipitation patterns. For the Pacific Northwest, La Niña often brings wetter and colder winters, with increased snowfall in mountainous regions.

“It’s totally not clear why this La Niña is so late to form, and I have no doubt it’s going to be a topic of a lot of research,” said Michelle L’Heureux, head of NOAA’s El Niño team. The delayed onset of La Niña may be linked to unusually warm global ocean temperatures over the past few years, which could have masked its development.

In the Pacific Northwest, La Niña is already making its presence felt. While snowpack levels in the Washington Cascades are close to normal, some areas, such as Cougar Mountain and Mount Gardener, are significantly below average, with only 20-30% of the typical snowpack water equivalent. This variability highlights the localized impacts of the climate pattern.

Globally, La Niña tends to cause drier conditions in the southern United States and wetter weather in parts of Indonesia, northern Australia, and southern Africa. It also increases the likelihood of Atlantic hurricanes during summer months. However, L’Heureux predicts that this La Niña event will be weak and short-lived, potentially dissipating by spring 2025.

The current La Niña is unusual not only for its late arrival but also for its expected brevity. Long-term climate models suggest the event could end as early as February, with El Niño conditions likely to dominate later in 2025. This rapid transition raises questions about the influence of climate change on traditional ENSO patterns.

“The global oceans have been running much, much warmer than average for more than a year, which might have had a hand in La Niña’s delay,” L’Heureux explained. Scientists are still researching the implications of these warmer ocean temperatures on ENSO development and its global impacts.

As the Pacific Northwest braces for a wetter winter, the broader implications of this La Niña event remain uncertain. Researchers continue to study how climate change may be altering long-standing weather patterns, leaving many questions unanswered for now.