News

Cape Town’s Caracals: A Balancing Act in a Changing Ecosystem

CAPE TOWN — A sharp crack reverberates through Constantia‘s forested area as volunteers employ air guns to redirect a wandering group of baboons away from a wealthy Cape Town suburb, located within their ancestral habitat. The Cape baboons (Papio ursinus) thrive in the region, yet their access to high-calorie human food and a lack of natural predators have led to a significant increase in their numbers, resulting in frequent conflicts with the city’s residents.

Gabriella Leighton, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cape Town, describes the city as part of a “complex” ecosystem. With almost 5 million residents, Cape Town is situated within the Cape Floral Kingdom, a renowned biodiversity hotspot. As anthropogenic alterations continue to affect the ecosystem, confrontations between wildlife and humans have become inevitable.

Leighton, who specializes in urban ecology and carnivore conservation, characterizes the Cape Peninsula as a natural laboratory. Recently, she published findings on local caracals (Caracal caracal), medium-sized wildcats known for their distinctively tufted ears, preying on marine birds such as endangered Cape cormorants (Phalacrocorax capensis) and African penguins (Spheniscus demersus). This shift in diet likely stems from extensive human-driven changes escalating since European settlers arrived.

Historically, the Cape Peninsula was abundant with wildlife, including elephants, black rhinos, lions, leopards, and caracals. The European settlers, led by Jan van Riebeek in 1652, brought numerous changes resulting in the eradication of several species such as hippos from the peninsula by the 1700s, and the complete extinction of others like the quagga and blue antelope.

“It’s a fascinating place,” notes Deborah Winterton, regional science liaison officer for South African National Parks (SANParks). Nonetheless, she acknowledges it as a disrupted system where ecological balance is lacking due to urban expansion that has rendered the Cape Peninsula an ecological island.

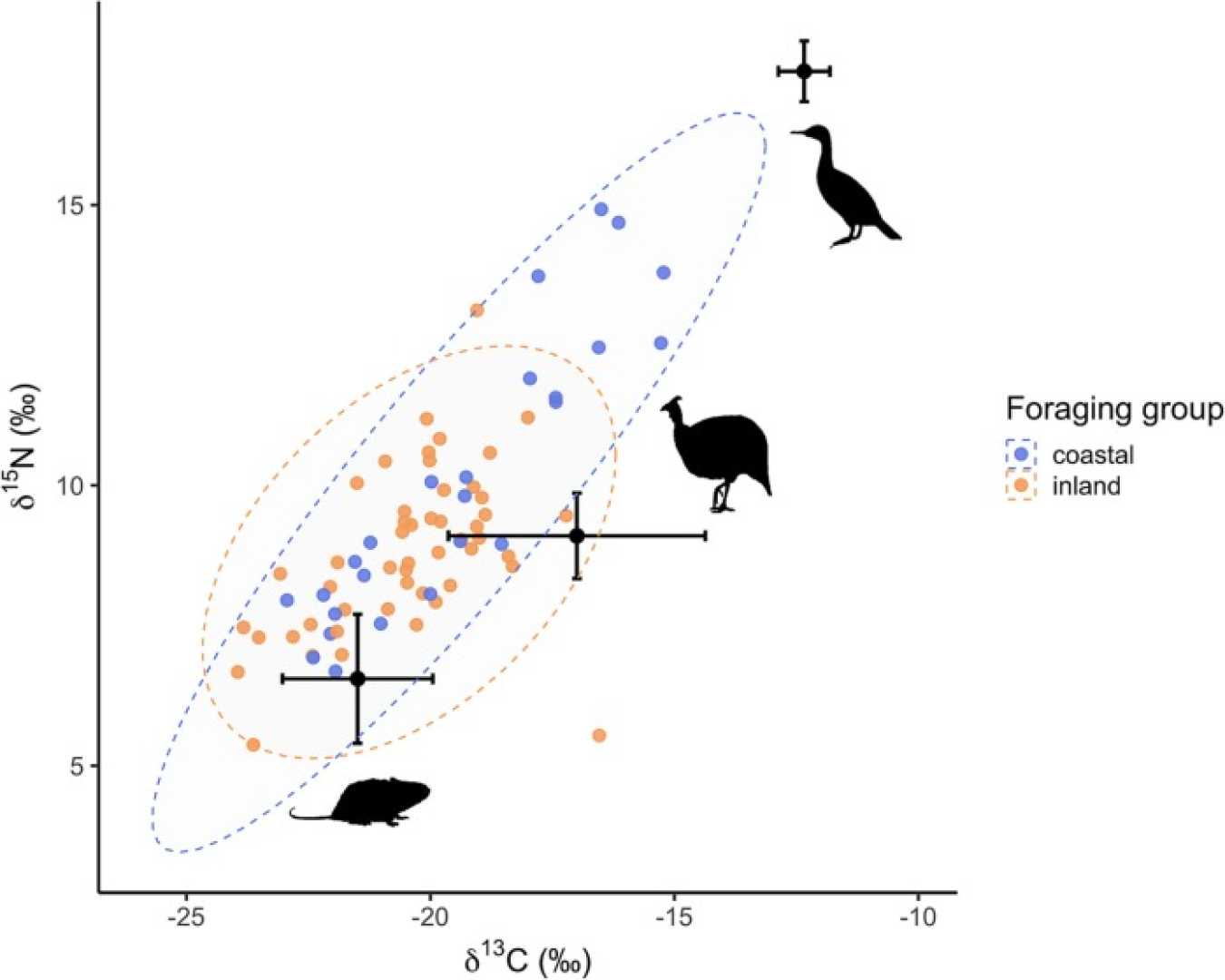

In this ever-changing habitat, species must adapt quickly to survive. Caracals, as top predators following the demise of lions and leopards, exhibit dietary flexibility, feeding on a diverse array of over 70 identified species. Recently, a significant portion of their diet includes seabirds, which they hunt in coastal areas.

African penguins, initially island-breeders, began nesting on the mainland in the 1980s, possibly due to food scarcity or overcrowding at their birth colonies. Christina Hagen, a penguin conservation biologist at BirdLife South Africa, notes their choice of Boulders Beach might have been influenced by existing seabird colonies indicating suitability.

The increase of mainland seabird colonies is partly attributed to improved coastal protections, yet it also presses these birds into the domains of native predators like caracals. While caracals benefit from these nutrient-rich meals, they also consume pollutants, raising concerns about their long-term health and ecological fitness.

Leighton mentions that pollutants such as arsenic, mercury, and selenium, present in offshore-feeding seabirds, expose caracals to potential physiological hazards. Although difficult to quantify in wild populations, captive animal studies suggest significant detrimental impacts.

Aside from dietary challenges, caracals face urban threats like vehicle collisions, poisoning, and attacks from domestic pets. The isolated caracal population on the Cape Peninsula also suffers from reduced genetic diversity, heightening vulnerability to disease and pollution. Despite these challenges, conservationists, including Leighton, suggest the adaptability and presence of caracals in urban areas showcase the potential for conservation within cities.