News

Survivors of Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Struggle for Recognition, Justice

HAPCHEON, South Korea — On August 6, 1945, Lee Jung-soon was on her way to elementary school when the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Now 88 years old, she recalls the chaos that day. “My father was about to leave for work, but he suddenly came running back and told us to evacuate immediately,” she said, gesturing as if trying to push the memory away.

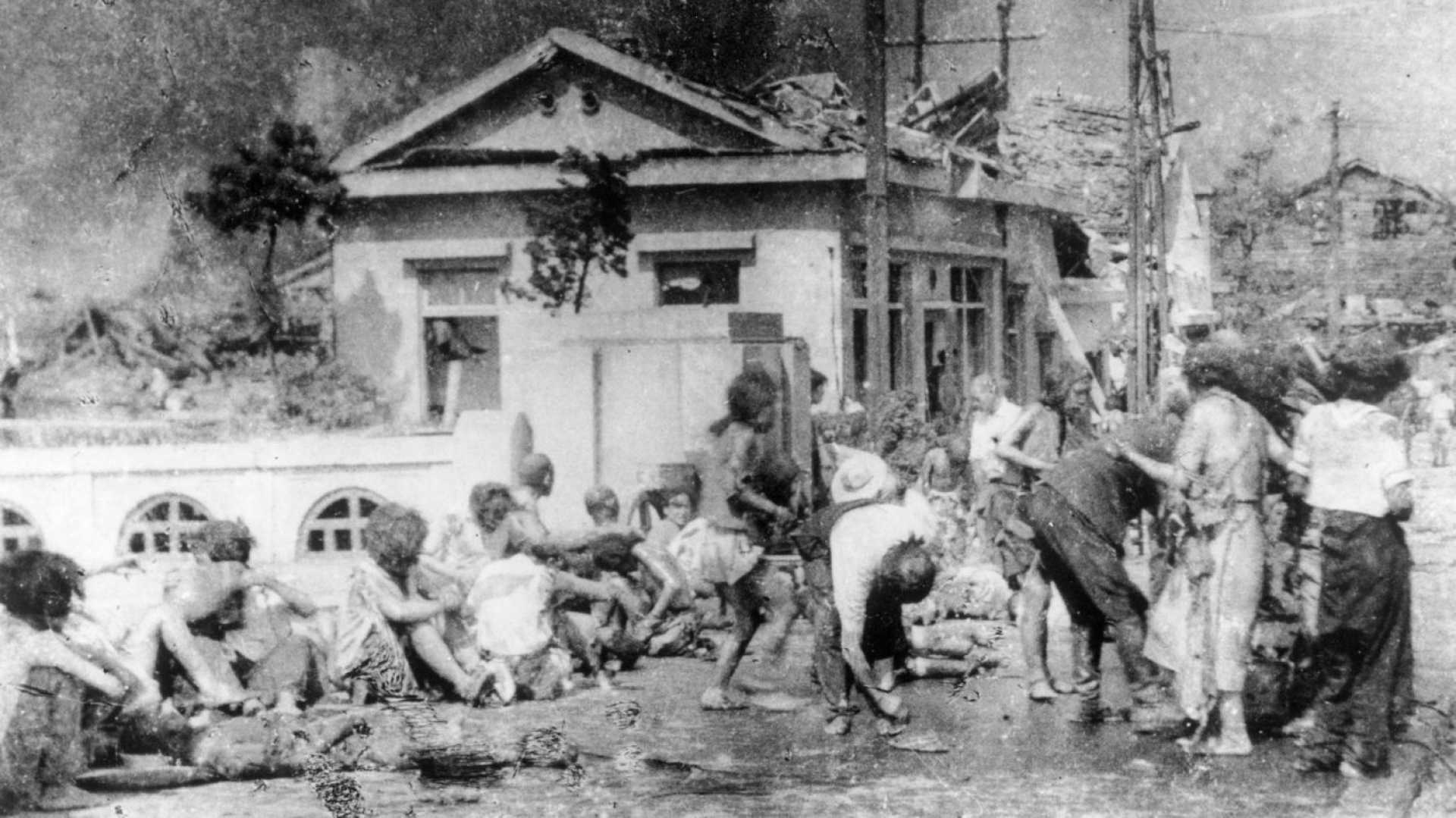

The explosion, equivalent to 15,000 tons of TNT, devastated Hiroshima, instantly killing around 70,000 people, many of whom were Korean laborers who had endured years of exploitation under Japanese rule. An estimated 20% of immediate bomb victims were Koreans, many of whom were in the city due to forced labor.

“In our village, some people had their backs and faces so badly scarred that only their eyes were visible,” Ms. Lee recounted. Survivors like her live with the long-lasting impacts of radiation, including illnesses passed down to their descendants. “No one takes responsibility,” said Shim Jin-tae, an 83-year-old survivor. “Not the country that dropped the bomb. Not the country that failed to protect us.”

Mr. Shim, who also resides in Hapcheon, urges acknowledgment for the victims’ suffering. This small county has been dubbed “Korea’s Hiroshima,” housing many survivors like him and Ms. Lee. Mr. Shim recalls the aftermath where Korean workers had to clean up the dead after the bomb. “They eventually used dustpans to gather corpses and burned them in schoolyards,” he stated.

Both Mr. Shim and Ms. Lee face serious health issues. Ms. Lee suffers from skin cancer and Parkinson’s disease. Her son, Ho-chang, has kidney failure and is on dialysis. “I believe it’s due to radiation exposure, but who can prove it?” Ho-chang said, highlighting the challenges faced by their generation in seeking justice.

The South Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare is conducting studies to gather genetic data on survivors, with plans to potentially recognize second- and third-generation victims if the results are statistically significant. However, many remain skeptical of this recognition process.

Social stigma complicates the situation further. Returning survivors faced prejudice branded as “disfigured” or “cursed.” Han Jeong-sun, a second-generation survivor, reflects on the pain of being seen as different. “My son has never walked a single step in his life,” she shared. “But my circumstances are proof of our suffering.”

Despite findings indicating a higher vulnerability to illness among second-generation survivors, recognition remains elusive. Advocates argue that the victims’ stories must be acknowledged while they are still alive. “Memory matters more than compensation,” Mr. Shim stated. “If we forget, it’ll happen again.”

On July 12, 2025, Japanese officials visited Hapcheon for the first time to honor the memorial without any formal apologies. Peace, according to activists like Junko Ichiba, requires acknowledgment of past wrongs. “Peace without apology is meaningless,” she asserted, emphasizing the need for justice.