News

Artist Suse Lowenstein Reflects on Loss from Lockerbie Tragedy

MONTALK, New York — Suse Lowenstein was deep into creating a new sculpture in her home studio when a tragic phone call shattered her world forever. The date was December 21, 1988, just days before Christmas, when a friend reached out to ask about her son, Alexander, who was studying abroad in London.

“Pan Am Flight 103,” Lowenstein replied, only to hear the devastating news: the plane had exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing all 270 people on board. Lowenstein crumpled in shock on the studio floor, whispering “no, no” as she came to terms with the unimaginable loss.

Alexander was among 35 Syracuse University students on the flight, and his tragic death marked one of the deadliest terrorist attacks against U.S. civilians before September 11, 2001. A Libyan terrorist was later convicted of the bombing that claimed 190 American lives. As investigations continue into additional suspects, the pain of that day remains ever-present for Lowenstein.

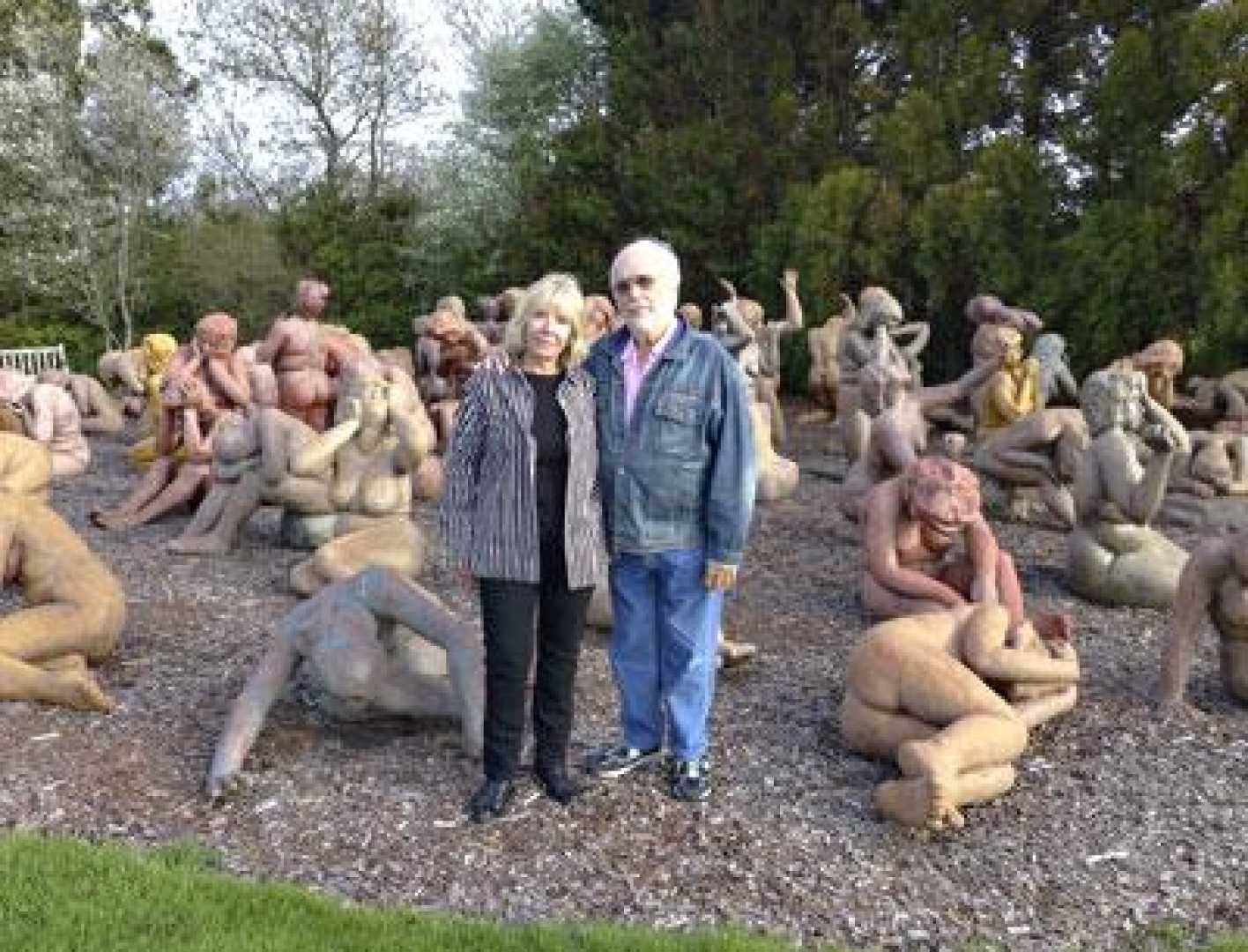

Nearly four decades later, Lowenstein channels her grief into art. Over the years, she has created a large sculptural installation called Dark Elegy, portraying the raw emotion of 76 women who lost loved ones in the Lockerbie disaster. The piece serves both as a tribute to those lost and a symbol of collective grief for women.

“You never forget that instant in which you are told… the exact feeling, the posture of your body. It is what is depicted in Dark Elegy,” Lowenstein articulates, suggesting that the grieving process is a never-ending journey. “In my case, I made it part of who I am and part of me. It’s inside of me. I live with it. I go with it. I make it mine.”

In her Montauk home, Lowenstein preserves the red jacket Alexander wore on the day he boarded the ill-fated flight, now tattered and scarred by flames. The label bearing the letter “A” for Alexander remains unobscured. Lost without her son, Lowenstein recalls the agony of those first moments after hearing the news.

“I knew he was gone the moment I received the phone call,” she lamented. Days later, the release of the passenger list confirmed her worst fears.

Alexander had just begun his journey through life, studying English at Syracuse University shortly before his death. A bond over a spontaneous trip to Germany had strengthened their relationship just weeks prior. “I was overcome with this incredible need to go over to London and be with him,” Lowenstein remembers, feeling thankful for that time spent together.

Lucas Lowenstein, Alexander’s younger brother, also grappled with the aftermath of loss. At that time, the siblings were navigating typical sibling conflicts. “The last thing we said to one another was that we hated one another,” Lucas recalls, reflecting on the bittersweet nature of their last conversation.

The tragedy left Lucas as the sole child in the family, burdened with survivor’s guilt that permeated his life. “I miss him… especially as our parents got older,” Lucas adds, underscoring the national tragedy’s personal dimensions.

In the wake of the bombing, Suse Lowenstein often found herself tormented by questions about her son’s last moments aboard the flight. “For days we wondered… what would remain of our beautiful son?” she contemplated, before expressing relief that Alexander’s body was ultimately found intact.

Scottish authorities slowly recovered belongings from the crash site, returning some items to the grieving families, including Alexander’s British rail pass and several pages from his diary, which opened a brief window into his last days. His entries described love interests and family relationships, evoking memories for his parents.

Now, nearly 35 years later, the Lowensteins gather every February 25 to commemorate Alexander’s birthday, sharing meals that reflect his vibrant spirit. In her yard, Suse has installed her Dark Elegy, a reminder of sorrow and resilience.

“It was a very delicate process,” she describes while recalling the emotion-filled sessions with other grieving women. Lowenstein invited 75 women to step onto platforms, allowing them to recreate their immediate anguish upon receiving tragic news. Each woman was inscribed in the sculptures with the names of their loved ones.

Today, Dark Elegy stands as both an artistic expression of grief and a communal space for remembrance, allowing those who lost loved ones in the Lockerbie bombing to find solace and connection within shared trauma.