News

La Niña Arrives, Impact on Weather Patterns and Hurricane Season Uncertain

WASHINGTON (AP) — La Niña, the cooler counterpart of El Niño, has arrived, affecting global weather patterns, meteorologists announced on Thursday. This phenomenon can often intensify the Atlantic hurricane season, but its current strength appears weak and may not lead to significant issues.

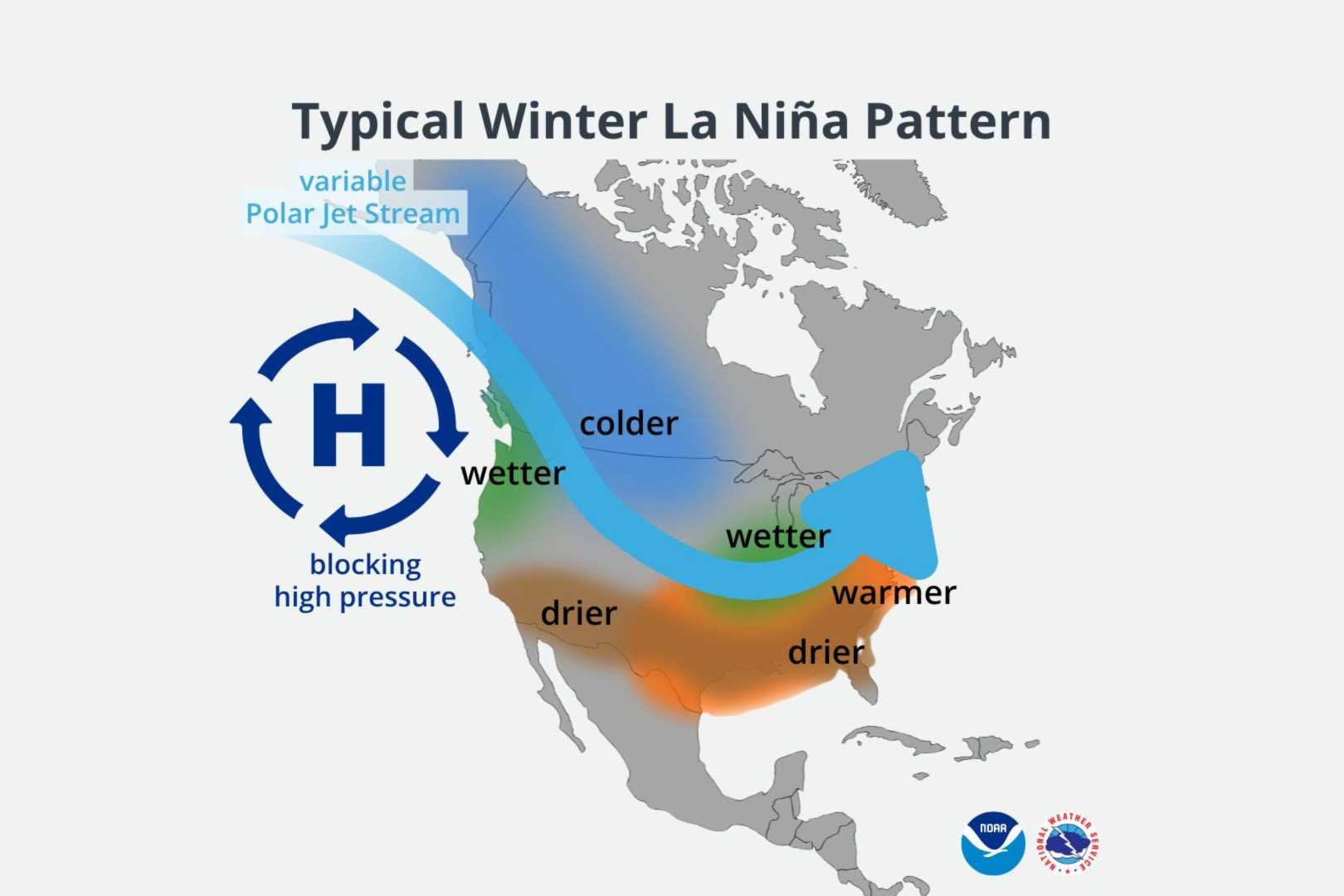

La Niña typically results in increased precipitation—including snowstorms—in northern U.S. regions, while southern areas may experience drier conditions. It also influences weather globally, bringing heavy rains to parts of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Central America, and causing droughts in eastern Argentina and China, according to experts.

A La Niña phase occurs when parts of the Central Pacific Ocean cool by 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit) compared to normal. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirmed La Niña conditions have formed, although forecasts indicate it may not remain strong for long.

“There is a three out of four chance it will remain a weak event,” said Michelle L’Heureux, lead scientist at NOAA. “A weaker event tends to exert less influence on the global circulation, so surprises could be expected.”

The 2025 Atlantic hurricane season has shown mixed activity levels. Brian Tang, a hurricane expert from the University of Albany, noted that La Niña usually reduces wind shear, fostering more significant storm development late in the year. However, other experts like Brian McNoldy of the University of Miami argue that the current La Niña is too weak to cause much impact on hurricane formations.

Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane expert at Colorado State University, echoed concerns about this winter’s hurricane activity, stating that conditions favoring hurricanes do not show significant signs of development in the upcoming weeks.

Research has indicated that La Niña can sometimes be more costly than its warmer counterpart, El Niño. A study revealed that drought linked to La Niña has cost U.S. agriculture between $2.2 billion and $6.5 billion, far exceeding the $1.5 billion losses associated with El Niño.

Azhar Ehsan, a Columbia University scientist, noted that while La Niña isn’t always the more expensive climate pattern, it often proves to be in the U.S. context.

NOAA predicts that La Niña conditions may persist through December, but any significant effects could be limited. A weak event could reduce conventional winter weather impacts but still result in predictable weather patterns.

Federal forecasters plan to release the official winter outlook on October 16, while the NOAA Climate Prediction Center will continue to monitor ENSO conditions, providing updates as necessary.