Health

Study Reveals Dogs Track Valley Fever Spread Amid Climate Change Risks

DAVIS, Calif. — A new study reveals that dogs may serve as key indicators for understanding the rising threat of Valley fever, a fungal infection on the rise due to climate change impacts in the Western United States. Researchers from the University of California, Davis, found that the incidence of the disease in dogs has surged in recent years, potentially signaling future risks for humans.

Valley fever, also known as coccidioidomycosis, is caused by a fungus that flourishes in moist soils and becomes airborne during drought. Its spores can easily be inhaled, leading to infection. Changes in climate, exemplified by increasing heavy rains followed by prolonged drought, are creating optimal conditions for this disease.

“Dogs are sentinels for human infections,” said lead author Jane Sykes, a professor of small animal internal medicine at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. “They can help us understand not just the epidemiology of the disease but they’re also models to help us understand the disease in people.”

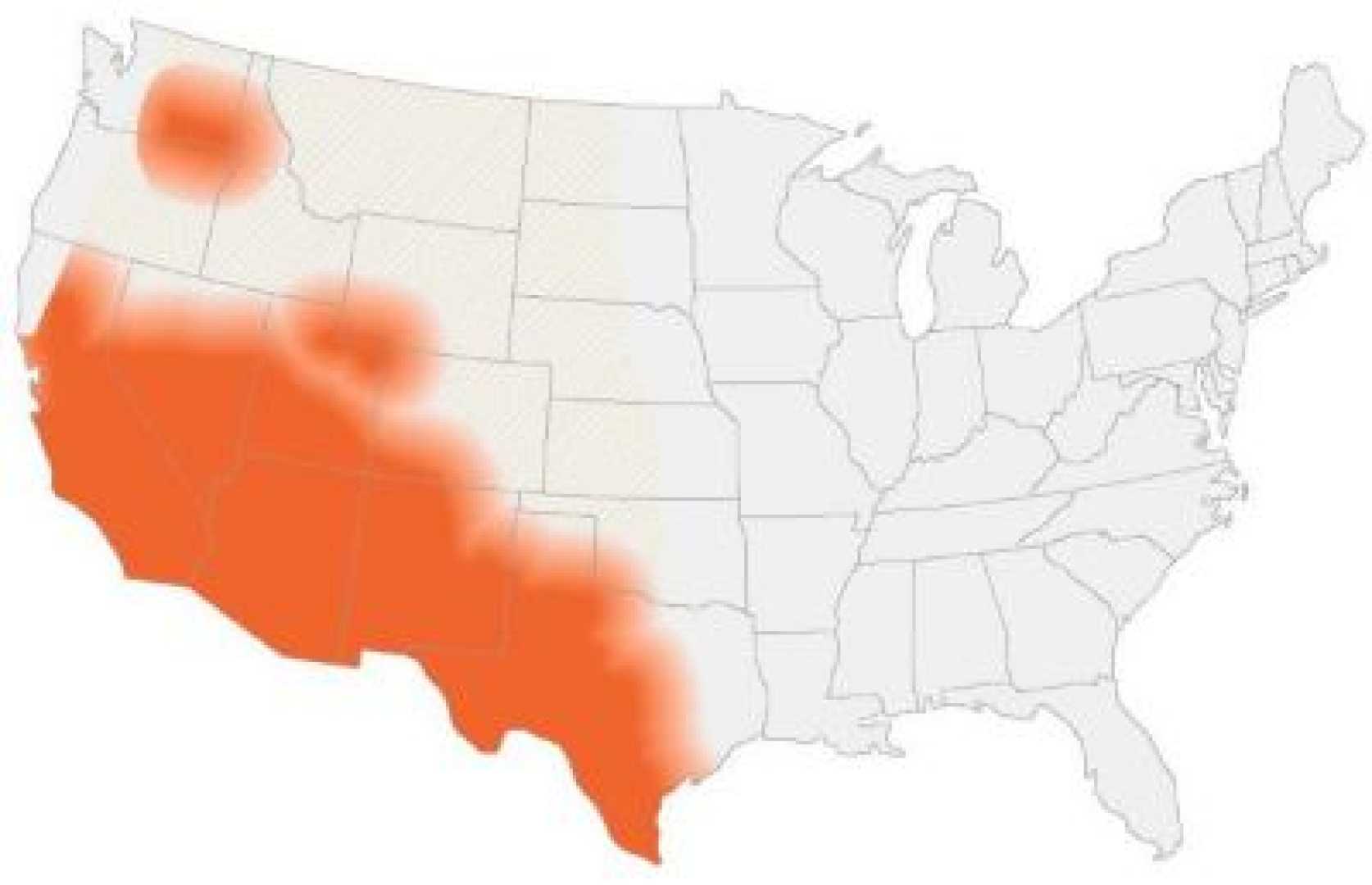

The research examined nearly 835,000 blood antibody tests from dogs across the country between 2012 and 2022. Astonishingly, nearly 40% of the tested dogs were positive for the infection. The study, published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, mapped positive results geographically and demonstrated an increase from 2.4% of U.S. counties reporting cases in 2012 to 12.4% in 2022.

“We were also finding cases in states where Valley fever is not considered endemic,” Sykes noted. “We should be closely watching those states because there could be under-recognition of the emerging fungal disease in humans.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) typically sees between 10,000 and 20,000 reports of human cases annually, but estimates suggest the actual number may be as much as 33-fold higher, as many states do not require reporting human cases. The CDC currently lists six states—Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah—as endemic areas for Valley fever.

Notably, the study identified Valley fever in dogs not only within these endemic states but also in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. “The sheer number of cases among dogs cannot be explained by their travel patterns, as they travel far less frequently than humans,” Sykes explained. “The dog cases correlated with human cases, including in known Valley fever hot spots.”

Arizona accounted for 91.5% of positive dog tests in the study, followed by California (3.7%), and the remaining endemic states collectively accounting for 2.6%. Arizona also revealed the highest incidence rate, with rates 100-fold greater than those in California, Nevada, and New Mexico.

Every state with more than 0.50 Valley fever tests per 10,000 households per year showed an increasing number of cases among dogs over the analyzed period. Dog breeds particularly prone to digging, such as terriers and medium-to-large breeds, face increased risk of contracting the disease, which can manifest similarly in dogs as it does in humans.

Symptoms may include coughing as the infection develops in the lungs, and in severe cases, the fungus can spread to bones, the brain, and the skin, requiring lifelong antifungal injections. Dogs can also die from Valley fever.

Sykes emphasized the potential value of dogs in understanding Valley fever better. “By learning more about Valley fever in dogs, scientists may discover new tests or treatments for the disease in humans,” she said. “Dogs could also help prevent misdiagnosis or undiagnosed disease in humans.”

Co-authors of the study include George Thompson III from UC Davis School of Medicine, and Simon Camponuri, Amanda Weaver, and Justin Remais from UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. Funding for the research was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.