Tech

Magnetic North Pole Drifts Toward Siberia, GPS Systems Updated

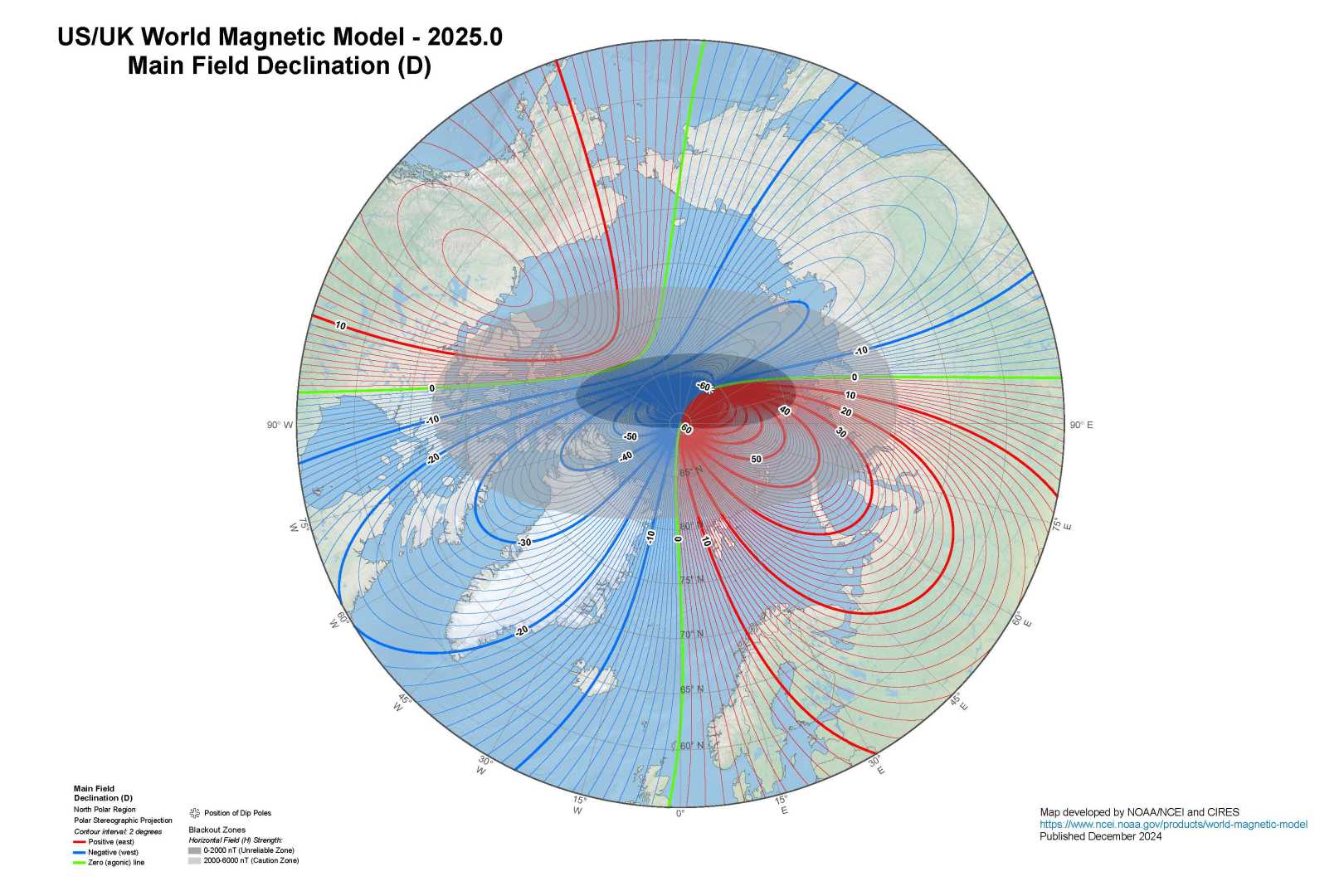

BOULDER, Colo. — Scientists have updated the World Magnetic Model (WMM) to reflect the latest position of the magnetic north pole, which has shifted closer to Siberia and continues to drift toward Russia. The update, released on December 17, 2024, ensures the accuracy of global positioning systems (GPS) used by planes, ships, and smartphones.

Unlike the geographic North Pole, which remains fixed, the magnetic north pole is determined by Earth’s ever-changing magnetic field. Over the past few decades, its movement has been erratic, accelerating dramatically before slowing down recently. Scientists remain uncertain about the underlying causes of these fluctuations.

“The more you wait to update the model, the larger the error becomes,” said Arnaud Chulliat, a senior research scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. “Our forecast is mostly an extrapolation given our current knowledge of the Earth’s magnetic field.”

The updated WMM includes two versions: a standard model with a spatial resolution of approximately 2,051 miles (3,300 kilometers) at the equator and a high-resolution model with a resolution of about 186 miles (300 kilometers). While the high-resolution model offers greater precision, most consumer GPS devices rely on the standard version.

“Major airlines will upgrade the navigation software across their entire fleets of aircraft to load in the new model, and militaries in NATO will need to upgrade software in a huge number of complex navigation systems across all kinds of equipment,” said William Brown, a geophysicist with the British Geological Survey. However, he noted that most individuals won’t need to upgrade their devices.

The magnetic north pole was first discovered in 1831 by British explorer Sir James Clark Ross in northern Canada. Since then, it has drifted steadily toward Russia, moving at an average rate of about 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) per year. However, its speed has varied significantly in recent decades, reaching a peak of 34.2 miles (55 kilometers) per year in the 1990s before slowing to 21.7 miles (35 kilometers) per year by 2015.

Scientists attribute the pole’s movement to the dynamic nature of Earth’s magnetosphere, which is generated by the churning of molten metals in the planet’s core. This constant motion ensures that the magnetic north pole is never static.

While the current drift is expected to continue slowing, scientists caution that the rate could change unexpectedly. “It could change its rate, or even speed up again,” Brown said. “We will continue to monitor the field and assess the performance of the WMM, but we do not anticipate needing to release a new model before the planned update in 2030.”

Earth’s magnetic field has undergone dramatic changes in the past, including complete reversals of polarity. These events, which occur roughly once every million years, can take thousands of years to complete and disrupt navigation systems, satellite operations, and animal migration patterns. The last major reversal occurred approximately 780,000 years ago.

“We’ve never experienced a reversal when modern technology was present,” Brown said. “It would certainly be an interesting time for engineers to adapt our technology to, but hopefully one they’d have a slow, centuries-long build-up to, rather than any sudden change.”