Health

Study Reveals Long-Term Health Risks of Wildfire Smoke Exposure

Seeley Lake, Montana – A wildfire lasting 49 days in 2017 left residents of Seeley Lake breathing smoky air, causing serious health concerns. Christopher Migliaccio, an associate professor of immunology at the University of Montana, led a study to assess the long-term effects of wildfire smoke exposure.

After securing funding, Migliaccio and his team monitored the lung function of local residents for two years. Surprisingly, they found that detrimental effects did not appear immediately but instead emerged over time. Initially, around 10 percent of participants showed reduced lung function, and most continued to experience these issues two years later.

“We were very surprised,” Migliaccio said, explaining that their research indicated prolonged exposure might pose greater risks than originally thought. The study’s continuation was hampered by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, prompting researchers to experiment with mice in controlled settings, yielding similar findings.

The frequency of wildfires has increased dramatically in the U.S., leading to more people continually exposed to smoke. Joan Casey, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of Washington, emphasized this changing landscape, stating, “It is the exposure that is impacting air quality across the U.S. now more than any other pollution source.”

Despite increased research, the long-term consequences of wildfire smoke exposure remain unclear. “We’re in the preschool stage of development,” Casey noted, highlighting the need for further studies.

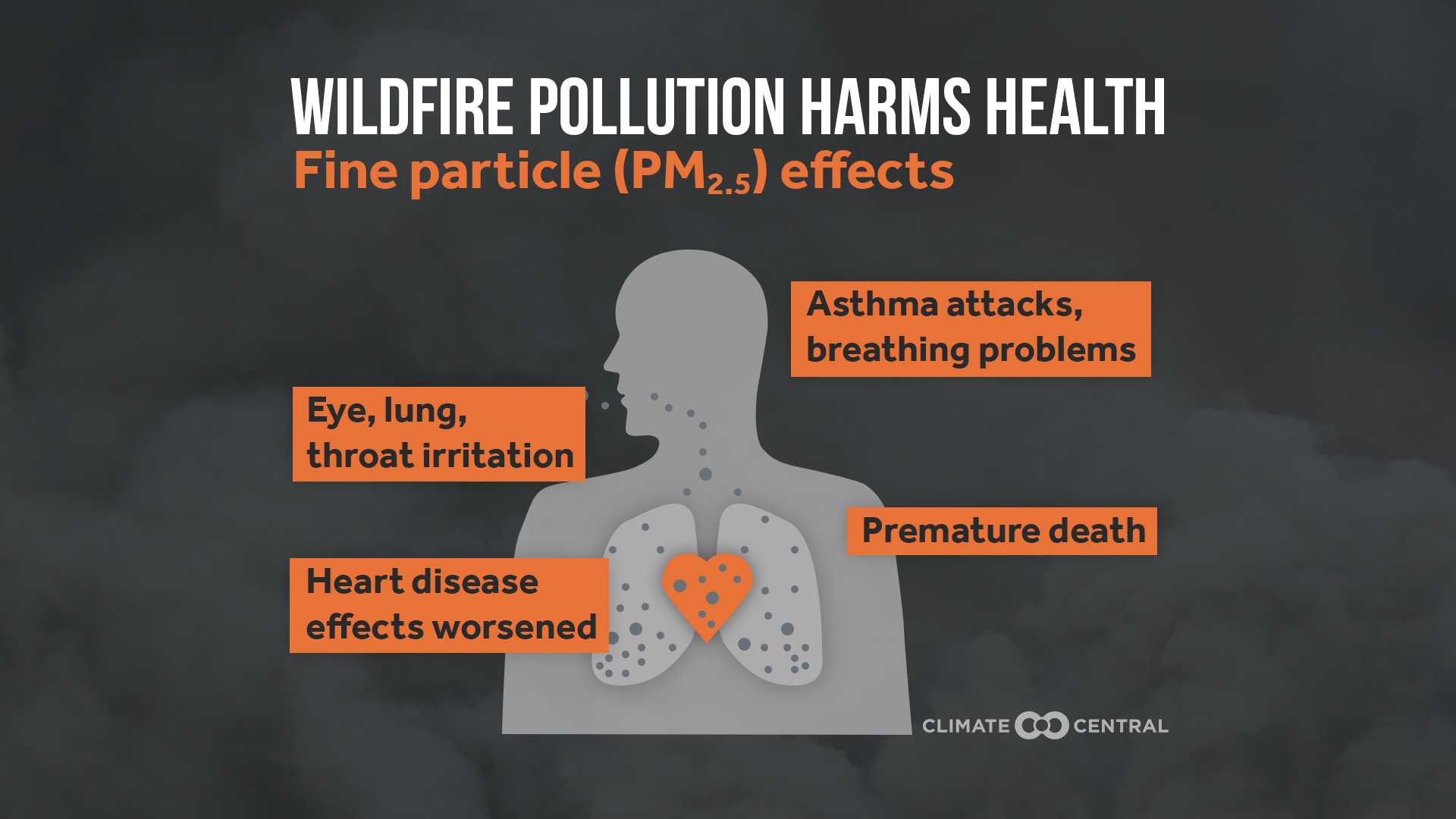

Research has shown that short bursts of exposure can lead to respiratory distress and long-term heart conditions. However, the accumulating impact of repeated smoke exposure, especially over a lifetime, is still not well understood. “Very little,” Marianthi-Anna Kioumourtzoglou, an environmental engineer from Brown University, said when asked about existing knowledge on health consequences.

Past studies have examined effects on animals, such as a 15-year study on rhesus monkeys, which indicated impaired lung function and immune response after exposure to wildfire smoke. Additionally, a study following firefighters is underway to explore potential impacts on fertility due to prolonged smoke exposure.

While the immediate health risks are evident, science has yet to fully uncover the long-term dangers posed by wildfire smoke, including its links to serious diseases like cancer and neurological disorders. Current models to study smoke exposure are flawed and lack comprehensive data, creating an urgent need for better research methods.

As climate change intensifies wildfire activity and smoke continues to plague populations, scientists like Susan Cheng at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center aim to track health outcomes in individuals exposed to smoke over time. “We really need to be closely tracking and following this,” Cheng warned, stressing the importance of understanding wildfire smoke’s long-term effects.